A pharmacopeia, in the modern sense, is a list of drugs and medicinal preparations, serving as an authoritative source of identification and a standard to be followed. Before the emergence of these works, however, medicines were described together with other treatments as part of general medical texts. Some were depicted in herbals and others in the materia medica books, with traditional medical remedies.

The first real pharmacopeia was, Pharmacorvm Omnivm, published by Valerius Cordus in 1546. Recognized as the official standard in Nurenberg, it inspired a chain reaction as many other European cities published their own local pharmacopeias. By the mid-17th century, this movement reached its peak, and the need to expand the jurisdiction of disparate pharmacopeias resurfaced. This eventually led to development of a standard for an entire country. The Pharmacopeia of the United States of America (Boston 1820) exemplifies this trend.

Publication of the Pharmacopœia Londinensis in 1618, a work widely disseminated in Europe through a multitude of foreign reprints, translations, and adaptations, illustrates another important aspect: authority. Backed by the Royal College of Physicians, the creation of this pharmacopeia was no longer one author’s responsibility. As time passed, institutional authority gradually shifted from societies (“colleges”) of physicians, to societies of pharmacists, or to governments responsible for producing national pharmacopeias.

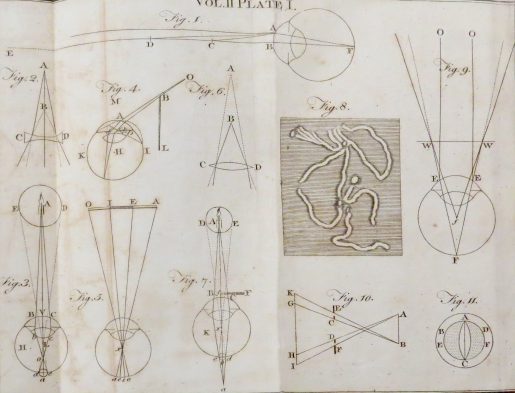

The 18th century brought another important trend in the development of the modern pharmacopeia: an increased focus on scientific evidence. This was triggered by progress in the sciences, especially chemistry. It led to a reduction of listing remedies associated with superstitions or customs, and to greater interest in the testing of drugs. All of these changes happened slowly, and though the displacement started in the Age of Enlightenment, some traditional medicinal remedies persisted in pharmacopeias until the late 19th century.

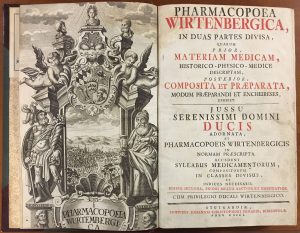

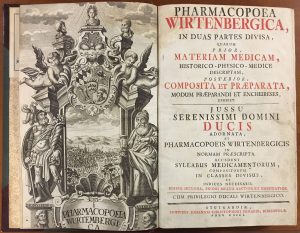

Falk Library has original or facsimile editions of the texts mentioned above along with the beautifully preserved Pharmacopoea Wirtenbergica (Stuttgart 1750) pictured here. It served as a standard for the Duchy of Württemberg. This book is an example of a pharmacopeia combining a formulary and a textbook giving comprehensive information about the materia medica in addition to the required listings.

For more information or to view these volumes, e-mail techserv@pitt.edu or call 412-383-9773.

~Gosia Fort

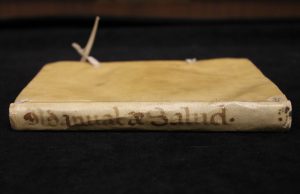

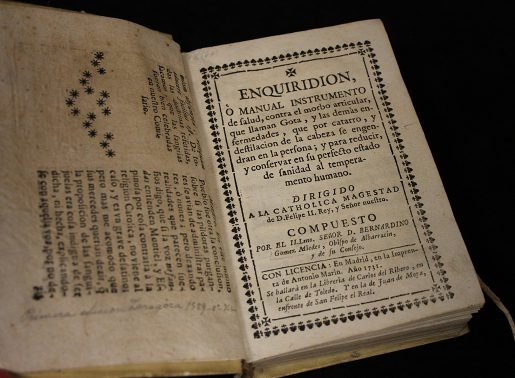

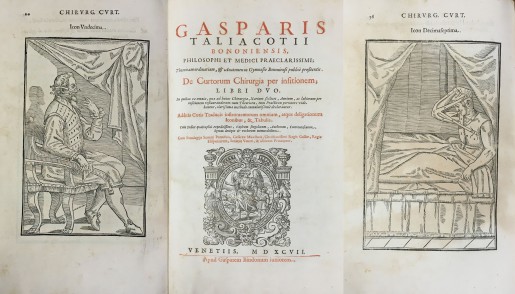

Bernardino Gómez Miedes (1520-1589) was a Spanish humanist well-versed in many disciplines. He authored two important books: Commentarii de sale (1572), the earliest discussion of salt, and Enchiridion (1589), a manual about gout. An edition of the latter, published again in Madrid in 1731, caught the eye of Dr. Gerald Rodnan. Dr. Rodnan was an avid book collector, professor of medicine, and the former division chief of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, who donated his impressive collection of rheumatology books to the Falk Library.

Bernardino Gómez Miedes (1520-1589) was a Spanish humanist well-versed in many disciplines. He authored two important books: Commentarii de sale (1572), the earliest discussion of salt, and Enchiridion (1589), a manual about gout. An edition of the latter, published again in Madrid in 1731, caught the eye of Dr. Gerald Rodnan. Dr. Rodnan was an avid book collector, professor of medicine, and the former division chief of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, who donated his impressive collection of rheumatology books to the Falk Library.

The idea of preserving memories, special moments, and histories in albums using scraps such as prints, bookplates, quotes, poems, calling cards, paper cutouts, press clippings, and photographs is not a new concept. In the United States, with the invention of photography and the appearance of a variety of patented photography and scrapbook albums, scrapbooking gained popularity in the 19th century. Today’s renewed interest in genealogy keeps the art of scrapbooking alive.

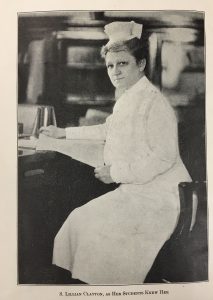

The idea of preserving memories, special moments, and histories in albums using scraps such as prints, bookplates, quotes, poems, calling cards, paper cutouts, press clippings, and photographs is not a new concept. In the United States, with the invention of photography and the appearance of a variety of patented photography and scrapbook albums, scrapbooking gained popularity in the 19th century. Today’s renewed interest in genealogy keeps the art of scrapbooking alive. Sarah Lillian Clayton (1874-1930) was a nurse and a Superintendent of Nurses at Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). She graduated from PGH Training School of Nursing in 1896 and began a nursing career that took her to Dayton, Minneapolis, and Chicago, only to return and complete her career in Philadelphia where she started. She became a national leader in nursing education, active in many organizations, and served as president of the National League for Nursing Education (1917-1920) and the American Nurses Association (1926-1930).

Sarah Lillian Clayton (1874-1930) was a nurse and a Superintendent of Nurses at Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). She graduated from PGH Training School of Nursing in 1896 and began a nursing career that took her to Dayton, Minneapolis, and Chicago, only to return and complete her career in Philadelphia where she started. She became a national leader in nursing education, active in many organizations, and served as president of the National League for Nursing Education (1917-1920) and the American Nurses Association (1926-1930).

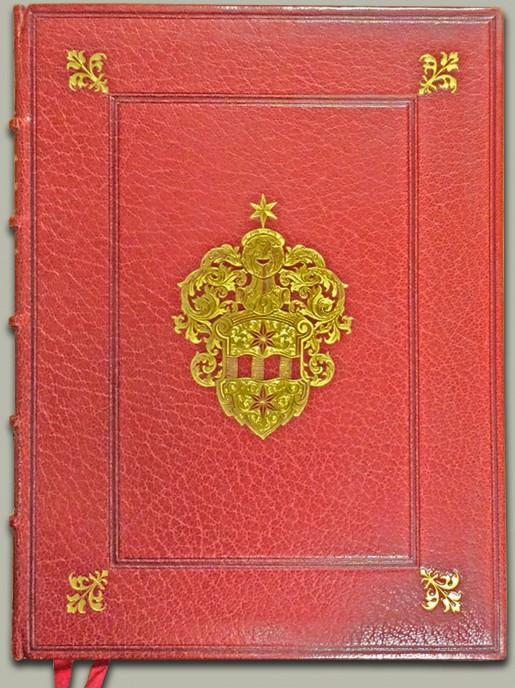

The Parisian bookbinding workshop later known as Gruel & Engelmann was founded in 1811 by Isidore Desforges. Desforges took his son-in-law Paul Gruel into partnership in 1825. After Gruel’s death in 1846, his widow Catherine, successfully continued the business. She had exquisite artistic taste and attracted the best talent to her workshop. It was a meeting place for all important binders of the time, and her salon became a literary club for celebrated collectors of books and bindings. Catherine won the highest prize at the Paris Exhibition in 1849, and repeated this success in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London where she won the gold medal for excellence of workmanship.

The Parisian bookbinding workshop later known as Gruel & Engelmann was founded in 1811 by Isidore Desforges. Desforges took his son-in-law Paul Gruel into partnership in 1825. After Gruel’s death in 1846, his widow Catherine, successfully continued the business. She had exquisite artistic taste and attracted the best talent to her workshop. It was a meeting place for all important binders of the time, and her salon became a literary club for celebrated collectors of books and bindings. Catherine won the highest prize at the Paris Exhibition in 1849, and repeated this success in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London where she won the gold medal for excellence of workmanship.

Herbals or herbaria—books describing herbs and their medicinal uses—are among the earliest literature created. They may be in the form of manuscripts, scrolls, codices, or loose sheets. Falk Library has several 18th century herbals, but the 1822 edition of John Hill’s Family Herbal is particularly interesting for three reasons: it has color plates unlike earlier herbals in our collection, it has an interesting provenance, and it was written by an author with a notorious reputation.

Herbals or herbaria—books describing herbs and their medicinal uses—are among the earliest literature created. They may be in the form of manuscripts, scrolls, codices, or loose sheets. Falk Library has several 18th century herbals, but the 1822 edition of John Hill’s Family Herbal is particularly interesting for three reasons: it has color plates unlike earlier herbals in our collection, it has an interesting provenance, and it was written by an author with a notorious reputation.