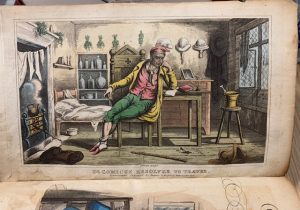

“The Adventures of Doctor Comicus or The frolics of fortune; a comic satirical poem for the squeamish & the queer in twelve cantos” was written by A Modern Syntax in the 19th century. It is a satirical poem about the amusing misfortunes of a poor country doctor during his trip to find a wife and to escape life as the all-in-one village barber, doctor, schoolmaster, and sexton. Whether it was a dream or a real escapade, it ended with Doctor Comicus’s sobering observation that,

“The Adventures of Doctor Comicus or The frolics of fortune; a comic satirical poem for the squeamish & the queer in twelve cantos” was written by A Modern Syntax in the 19th century. It is a satirical poem about the amusing misfortunes of a poor country doctor during his trip to find a wife and to escape life as the all-in-one village barber, doctor, schoolmaster, and sexton. Whether it was a dream or a real escapade, it ended with Doctor Comicus’s sobering observation that,

“Man in his eager haste to seize a bliss,

Which nature never destin’d should be his […]

He dreams of riches, grandeur, and a crown,

He wakes, and finds himself a simple clown.”

The author hiding under A Modern Syntax cleverly tied his pseudonym to the widely popular “Dr. Syntax” books, published between 1815 and 1828, that were written by William Combe and illustrated by famous British cartoonist Thomas Rowlandson. A Modern Syntax took advantage of the popularity that Dr. Syntax had earned as a hero through his peregrinations. At the same time, the original Dr. Syntax story was separated from the parody by using the label “modern.” A Modern Syntax introduced Doctor Comicus as a new hero who reaped the benefits of his predecessor’s fame. It was one of many imitations of Combe’s earlier parody.

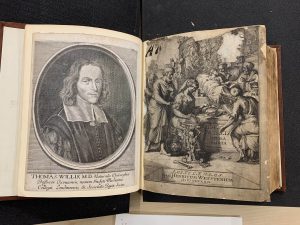

Thomas Willis (1621-1675) was a successful English physician, professor of natural sciences at Oxford, and a founding member of the Royal Society. He was an example of a physician who, instead of embracing classical authority, chose to study things based on direct observations. He was also the first to argue that research into the anatomy of the brain was the necessary foundation to speculations about the mind. Falk Library owns his work “Opera Omnia,” published in 1682 in Amsterdam by Henricus Wetstein.

Thomas Willis (1621-1675) was a successful English physician, professor of natural sciences at Oxford, and a founding member of the Royal Society. He was an example of a physician who, instead of embracing classical authority, chose to study things based on direct observations. He was also the first to argue that research into the anatomy of the brain was the necessary foundation to speculations about the mind. Falk Library owns his work “Opera Omnia,” published in 1682 in Amsterdam by Henricus Wetstein.

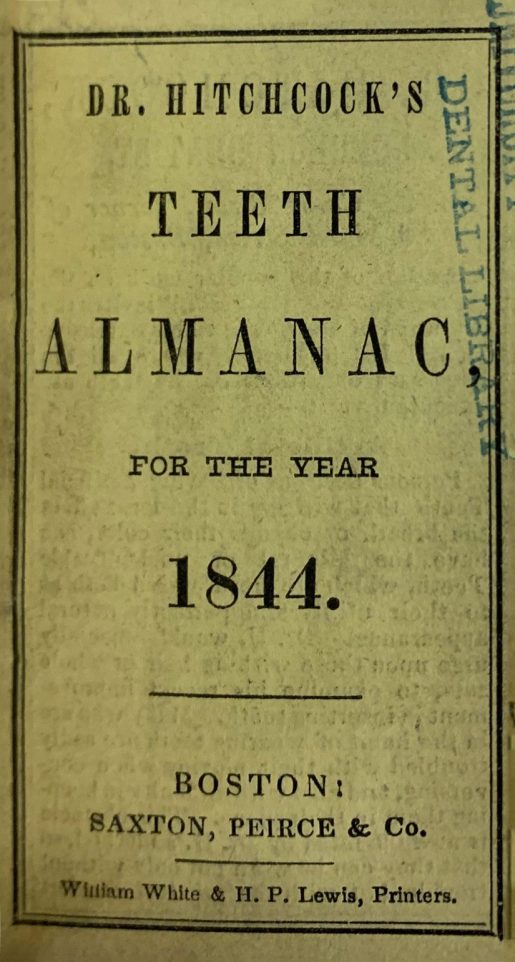

Today, the almanac is no longer the important and popular resource it once was in most households. It appeared in America at the end of the 17th century and its popularity was second only to the Bible. Almanacs offered lists of current events, advice, and weather prognostics tailored to a specific audience, such as that of the Farmer’s Almanac, and served as a basic home reference, especially for those in isolated households, helping to keep track of passing time. Dr. David Keyes Hitchcock started publishing almanacs annually around 1839, which happened years before printed calendars were invented (1870), and before there were any standards (1883)* by which to set clocks and watches.

Today, the almanac is no longer the important and popular resource it once was in most households. It appeared in America at the end of the 17th century and its popularity was second only to the Bible. Almanacs offered lists of current events, advice, and weather prognostics tailored to a specific audience, such as that of the Farmer’s Almanac, and served as a basic home reference, especially for those in isolated households, helping to keep track of passing time. Dr. David Keyes Hitchcock started publishing almanacs annually around 1839, which happened years before printed calendars were invented (1870), and before there were any standards (1883)* by which to set clocks and watches. Have you ever looked at the

Have you ever looked at the  Medals, unlike coins, or at times tokens, are not monetary instruments. They are frequently used to commemorate people, events, or things. As a perfect medium, and due to their permanence, they pass along information about past events and man’s achievements to future generations.

Medals, unlike coins, or at times tokens, are not monetary instruments. They are frequently used to commemorate people, events, or things. As a perfect medium, and due to their permanence, they pass along information about past events and man’s achievements to future generations.

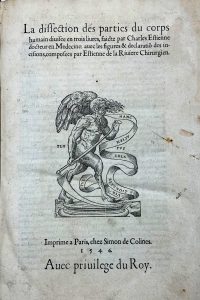

Charles Estienne (1504-1564) was a contemporary of Andreas Vesalius. He came from a family of Parisian printers and publishers. Estienne studied classical philology at the University of Padua in Italy, and upon his return to France, earned a medical degree at the University of Paris. He practiced medicine and taught anatomy at the Faculté de Médicine (1544-1547). His De dissectione partium corporis humani (1545) is often compared to the famous De humani corporis fabrica by Vesalius (1543). Estienne prepared anatomical drawings with the surgeon and artist Etienne de la Riviére. They partially printed the book in 1541, but its full publication was delayed due to a lawsuit in which both collaborators were involved. Had it appeared as planned, this work may have changed several “firsts” in medical history as claimed by Vesalius.

Charles Estienne (1504-1564) was a contemporary of Andreas Vesalius. He came from a family of Parisian printers and publishers. Estienne studied classical philology at the University of Padua in Italy, and upon his return to France, earned a medical degree at the University of Paris. He practiced medicine and taught anatomy at the Faculté de Médicine (1544-1547). His De dissectione partium corporis humani (1545) is often compared to the famous De humani corporis fabrica by Vesalius (1543). Estienne prepared anatomical drawings with the surgeon and artist Etienne de la Riviére. They partially printed the book in 1541, but its full publication was delayed due to a lawsuit in which both collaborators were involved. Had it appeared as planned, this work may have changed several “firsts” in medical history as claimed by Vesalius.

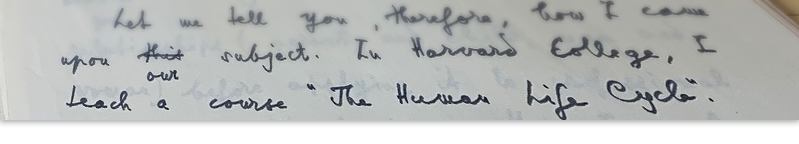

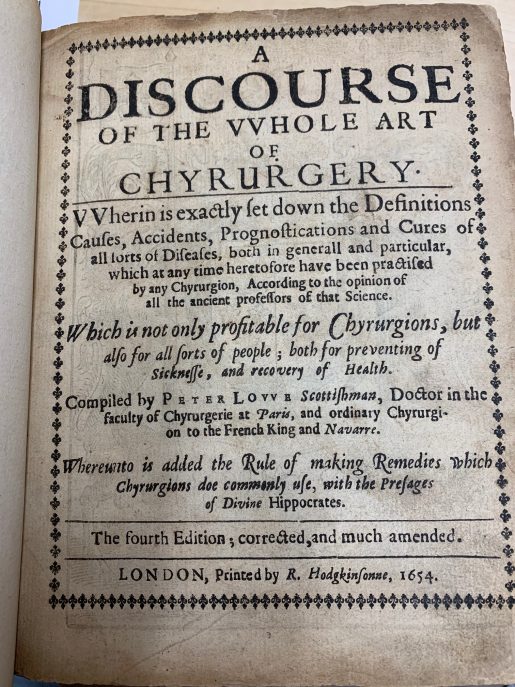

Peter Lowe, author of A Discourse of the Whole Art of Chirurgery published in London in 1654, left a significant mark on Scottish medicine by founding the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, reorganizing the practice of medicine in the same city, and then writing a book that made quite a stir. Contrary to the dominating trend at that time to write scientific books in Latin, this book was written in the vernacular and enjoyed great popularity (four editions in the 17th century). However, even more than its importance to 17th century medicine, are the provenance notes added in the 19th century that make the volume in Falk Library’s rare book collection special and unique.

Peter Lowe, author of A Discourse of the Whole Art of Chirurgery published in London in 1654, left a significant mark on Scottish medicine by founding the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, reorganizing the practice of medicine in the same city, and then writing a book that made quite a stir. Contrary to the dominating trend at that time to write scientific books in Latin, this book was written in the vernacular and enjoyed great popularity (four editions in the 17th century). However, even more than its importance to 17th century medicine, are the provenance notes added in the 19th century that make the volume in Falk Library’s rare book collection special and unique.