Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente (1537-1619) was an Italian surgeon and anatomist and one of the founders of modern embryology. He spent most of his life in Padua, eventually becoming chair of surgery and anatomy. During his long academic career he attracted students from all over Europe. Fabricius changed the teaching of anatomy by designing and using the first theater for public anatomical dissections. He  laid the foundation for modern anatomical illustration by focusing strictly on technical issues, and abandoned the backgrounds and artistic impressions present in his predecessors’ works. Fabricius also contributed to the development of comparative anatomy and surgery. He was the first to describe venous valves. Though he failed to see that they were proof of the circular motion of blood, his work may have inspired William Harvey’s De Motu Cordis.

laid the foundation for modern anatomical illustration by focusing strictly on technical issues, and abandoned the backgrounds and artistic impressions present in his predecessors’ works. Fabricius also contributed to the development of comparative anatomy and surgery. He was the first to describe venous valves. Though he failed to see that they were proof of the circular motion of blood, his work may have inspired William Harvey’s De Motu Cordis.

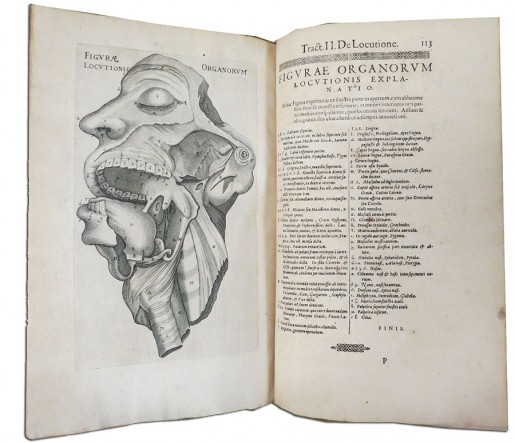

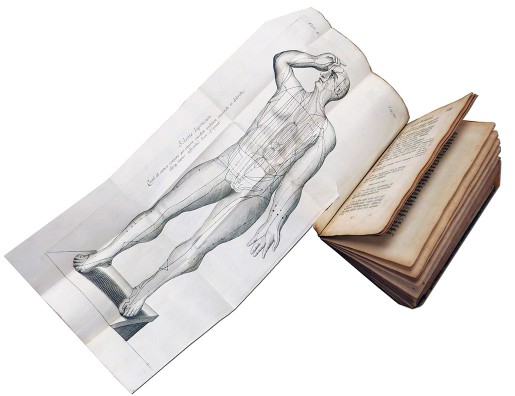

His posthumously published four treatises, Tractatus Quatuor (Frankfurt, 1624), includes his advanced embryology work on the formed fetus (De Formato Foetu);¹⁻² two texts on speech; and the treatise on venous valves. The book is bound in fine old leather, with a ribbed spine, gold lettering and decorative stamps. It has 41 copper plates including a spectacularly engraved title page with a dissection scene and images illustrating the organs of speech, inside the diaphragm, and an umbilical cord wrapped around the neck of a fetus.

The book can be viewed in the Rare Book Room by appointment.

~Gosia Fort

1. H. Gilson, “De Formato Foetu,” in Embryo Project Encyclopedia, August 27, 2008. http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1931.

2. S.L.M. Rosenberg, “Hieronymus Fabricius Ab Aquapendente: Parts I-III.” California and Western Medicine 38, no. 3-5 (1933):173-176, 260-263, 367-370.

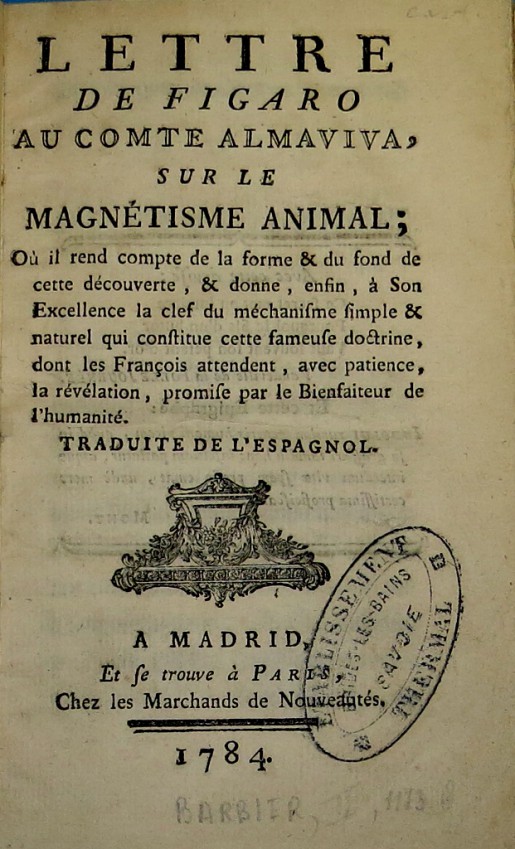

The tract was written to serve in the campaign against animal magnetism. It was focused on a popular topic, short lived, and tossed away when the interest in animal magnetism faded. Consequently, tracts are quite scarce. There are several copies of the second edition in the United States and France, but finding a first edition copy is very rare. Two identified copies, one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and one in the University of Oklahoma are of the same variety. A

The tract was written to serve in the campaign against animal magnetism. It was focused on a popular topic, short lived, and tossed away when the interest in animal magnetism faded. Consequently, tracts are quite scarce. There are several copies of the second edition in the United States and France, but finding a first edition copy is very rare. Two identified copies, one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and one in the University of Oklahoma are of the same variety. A

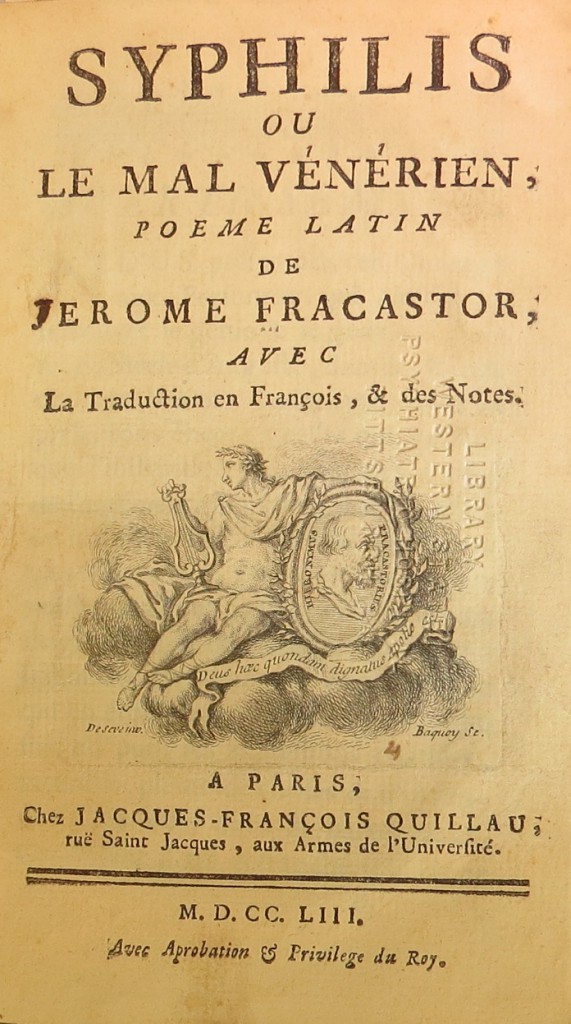

Syphilis ou le mal vénérien: Poeme Latin de Jerome Fracastor avec la traduction en François & des notes [Syphilis, or the venereal disease: the Latin poem of Girolamo Fracastoro with French translation & notes]. Paris, 1753

Syphilis ou le mal vénérien: Poeme Latin de Jerome Fracastor avec la traduction en François & des notes [Syphilis, or the venereal disease: the Latin poem of Girolamo Fracastoro with French translation & notes]. Paris, 1753

The antique amputation surgical set (c. 1890) was fabricated by George Tiemann of New York. The wooden case with a key lock is lined with purple velvet. The bottom compartment holds eight surgical knives, one artery forceps, five needles, an elastic bandage, and a tourniquet with an iron chain.

The antique amputation surgical set (c. 1890) was fabricated by George Tiemann of New York. The wooden case with a key lock is lined with purple velvet. The bottom compartment holds eight surgical knives, one artery forceps, five needles, an elastic bandage, and a tourniquet with an iron chain.

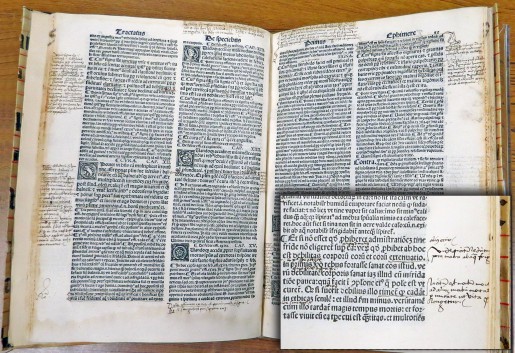

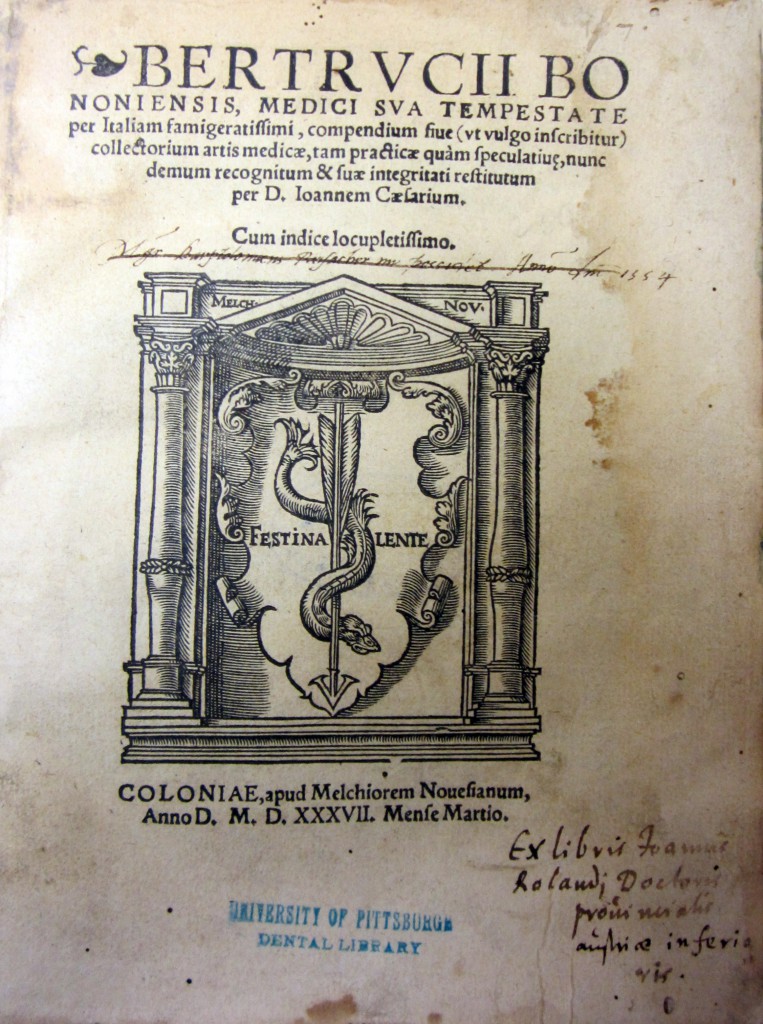

Little is known about Nicola Bertuccio (d. 1347), the author of the Compendium sive (ut vulgo inscribitur) Collectorium artis medicae, published in 1537. He was associated with the University of Bologna, a center in medieval Europe for the study of medicine, where dissection began to be practiced around 1300. Following the research of his teacher and predecessor, Mondino de Liuzzi, Bertuccio contributed to the revival of anatomical studies. His teachings attracted Guy de Chauliac, the author of a seminal work in surgery, Inventarium sive Chirurgia Magna, to come to Bologna to study surgical techniques.

Little is known about Nicola Bertuccio (d. 1347), the author of the Compendium sive (ut vulgo inscribitur) Collectorium artis medicae, published in 1537. He was associated with the University of Bologna, a center in medieval Europe for the study of medicine, where dissection began to be practiced around 1300. Following the research of his teacher and predecessor, Mondino de Liuzzi, Bertuccio contributed to the revival of anatomical studies. His teachings attracted Guy de Chauliac, the author of a seminal work in surgery, Inventarium sive Chirurgia Magna, to come to Bologna to study surgical techniques.

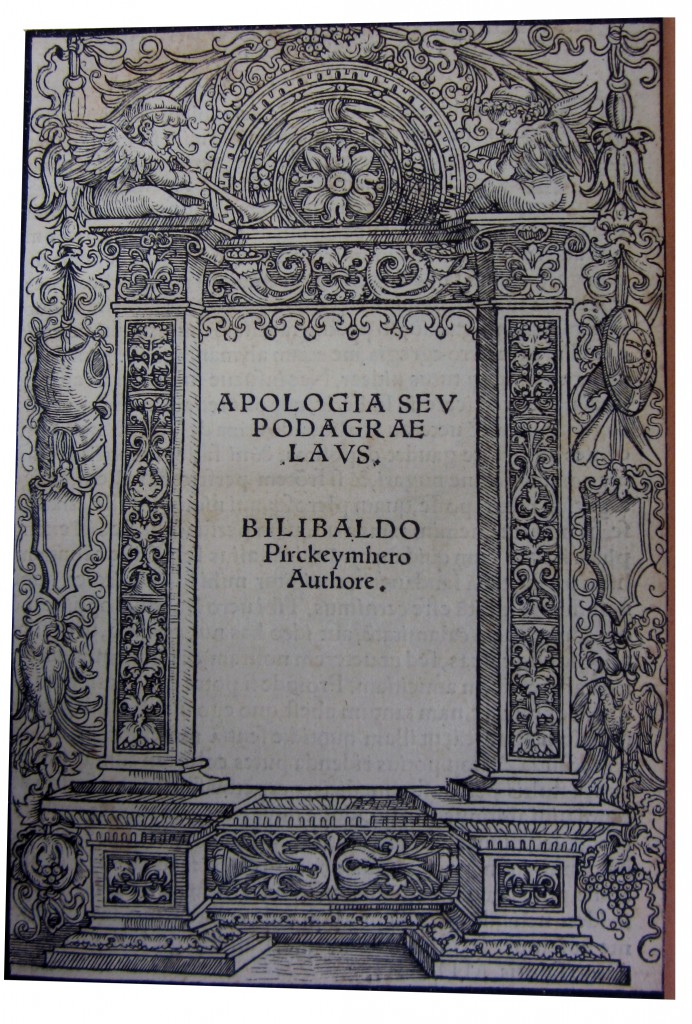

One of his later published works was Apologia seu Podagrae laus (Nuremberg 1522), an ironic praise of gout, from which he suffered. In this short witty eulogy to gout, Pirckheimer takes on the role of “woman gout,” in a literary game to settle scores with his enemies.

One of his later published works was Apologia seu Podagrae laus (Nuremberg 1522), an ironic praise of gout, from which he suffered. In this short witty eulogy to gout, Pirckheimer takes on the role of “woman gout,” in a literary game to settle scores with his enemies.