Listening to the sounds of the body is an old diagnostic technique, reported as early as the 16th century BC in an ancient Egyptian work known as the Ebers Papyrus. For centuries though, the only way to assess the sounds of the human body was to use an unaided ear on the patient’s chest. René Théophile Hyacinthe Laennec introduced mediated auscultation by inventing a stethoscope, a device to aid a physician in listening to the chest sound.

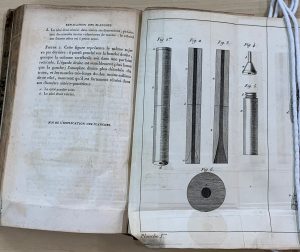

The invention was born in 1816 when the young doctor, reluctant to use a direct auscultation method on a person with a higher weight, rolled a piece of paper into a tube in the moment of need and carved the tool from wood shortly thereafter. The sound not only travelled through the improvised tool, but it was also easily and clearly audible. Thus, Laennec started to use the new device from that moment on.

The results of Laennec’s observations and practice became his seminal work “De l’auscultation médiate, ou, Traité du diagnostic des maladies des poumons et du coeur” [On mediated auscultation, or, Treatise of diagnostics in the diseases of the chest and heart], published in Paris in 1819. In this work, he described his stethoscope. He also correlated his observations of the diseased organs in many patients he examined using it with the findings from autopsies, which allowed him to offer a classification of cardiopulmonary disorders. Though initially the book and the stethoscope received a cool reception, by the 1826 publication of the second edition and subsequent translation into English, the use of the stethoscope was accepted. It became not only a standard tool but also a symbol of the physician. Laennec himself referred to his invention as “the greatest legacy of my life.”

After monaural stethoscopes (like the one invented by Laennec or the one illustrated here) came flexible, binaural, acoustic, and electronic stethoscopes. Evolution and improvement continued to the point that the use of the traditional stethoscope and the need to teach it are occasionally questioned by some, especially in light of the ease of use and the accuracy of reading the electronic devices. The devices and methods might change, but the need for auscultation and its help to diagnosticians remain unquestionable. Therefore, highlighting Laennec’s masterpiece and the invention of the stethoscope seems justified.

- Laennec’s “De l’auscultation médiate” (Paris 1819) with marble edge exposed.

- A plate with Laennec’s stethoscope from “De l’auscultation médiate” (Paris 1819).

The two-volume set held by Falk Library is not in perfect condition. The marble page edge finish is intact, and the original marble boards and leather spine were preserved, though the first volume had to be re-backed. The second volume still awaits repair. All plates are present, including a drawing of the first stethoscope. The copy comes from the library of Dr. James D. Heard and includes his personal note that it was purchased in Paris in 1909. It can be viewed in the Rare Book Room by appointment.

~Małgorzata Fort