When I started to write this column in 2010, I did not think it would last until my retirement. Yet, the HSLS collection is rich, and I always could find an interesting book or item to write about. The books as material objects fascinate me. Digitization efforts all over the world made many old texts from rare book collections accessible to users; however, not all aspects of physical books can be converted to a form available online. Nothing can replace the emotions of holding a 500-year-old book in your hand, feeling the thickness or roughness of the paper or the smoothness of the binding, smelling the old parchment, surveying with your own eyes the scars accumulated due to the passing of time and previous use, or uncovering the absolute unique features of the copy in your hand. Therefore, in my short articles, I always tried to bring this material aspect of the described book along with the historical value of the text. Choosing a book for this goodbye piece turned out to be challenging, because there are way too many items in the collection that I like and still want to introduce to readers. I settled for the iconic name in the history of medicine – Andreas Vesalius and his “De humani corporis fabrica” [On the fabric of the human body].

The first edition of the book, published in Basel in 1543, is without a doubt the most valuable item in the Falk Library collection. Currently, it is on exhibit in the Rare Book Room, and all visitors to the library can see it during the library’s open hours. My favorite “Fabrica,” among the many other editions that the library has, is the second edition, published in 1555. This “anniversary” piece (celebrating 15 years of “Treasures from the Rare Book Room” and 470 years since the publication of this book) will highlight the features that make my favorite copy special.

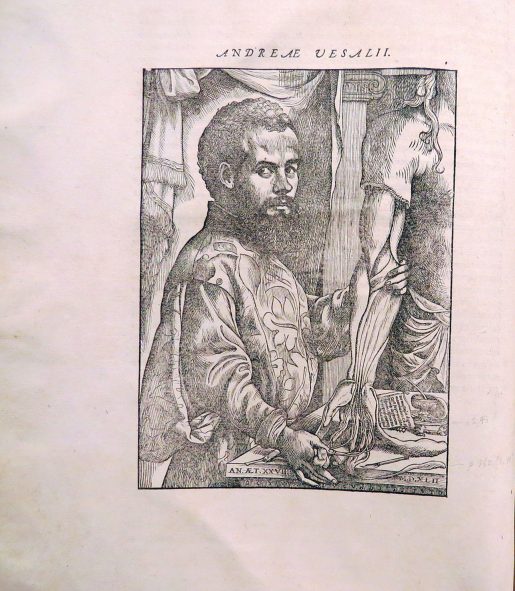

Like the first edition, the 1555 version was published by the same publisher and printer in Basel, Joannes Oporinus. It shares the same claim of being the work that challenged 13 centuries of Galen’s dominance in anatomy and began the era of modern anatomy. With it, Vesalius changed the knowledge and teaching of anatomy. He dissected human bodies to learn anatomy, which, paired with his attention to detail, allowed him to correct more than 200 of Galen’s errors. On top of this, he ensured that the accuracy, quality, and beauty of the woodcuts enhanced his discourse on anatomy. The woodcuts also include a portrait of Vesalius, a frontispiece with dissection, and historiated initials depicting medical procedures. It is an edition published during Vesalius’s lifetime, and the author was actively engaged in the printing process.

The handsome folio is bound in 17th-century half leather binding with paste paper boards and edges sprinkled with red and green. The spine has raised bands which divide it into eight sections, and a gilded author’s name is in two of them. Unfortunately, I was not able to piece together the full provenance of this copy, as the earliest owners whose signatures are on the book have not been identified, but it is certain that the New York Academy of Sciences and Dr. H.K. Corning were both former owners before the book was donated to the library in 1945. The copy has plenty of discrete annotations in German.

Hanson Kelly Corning (1860-1951) was an American physician and professor of anatomy at the University of Basel in Switzerland. He was instrumental in planning and building a new Anatomy Institute in Basel in the St. Johann district and moving it out of the historic Vesalianum building in St. Peter’s Square (1921). He was also the author of the “Textbook of Topographical Anatomy” [translated title] (1904). His notes in the described copy of “Fabrica” are in pencil. That is significant, because the annotations of contemporaries are usually in ink, a practice comparable to using a highlighter in a contemporary textbook. However, Dr. Corning was consulting and studying a book that was more than 300 years old, and the use of pencil is a sign of his respect for an old text.

Thus, my goodbye message to all is this: the rare books are meant to be used, so study them with care and reverence, and protect them by treating them with consideration, gentleness, and love. Let the next generation experience them, too.

~Małgorzata Fort