Falk Library’s facsimile of Anatomia depicta, published in Rome in 2010, replicates the original from the Florentine library. It is accompanied by a volume of commentaries (with transcription and translation of the manuscript), a wooden display case, and a protective plexiglass cover. It is the newest addition to HSLS Special Collections.

Filippo Cavriani (1536-1606), the author of Anatomia depicta, was born in Mantua to a prominent family. He was an Italian physician and humanist. Thanks to family connections, Cavriani was part of Cardinal Gonzaga’s entourage during the Council at Trent and spent some time with him in Prague before he became a private doctor to the Duke of Nevers, Ludovico Gonzaga. He was also associated with the court of Catherine de Medici and briefly served as the chief physician to the court of Henry III in Paris. However, his political ambitions got him in trouble with the king, and he returned to Italy in 1589. He held the chair of theoretical medicine at the University in Pisa, and for a while was happy to immerse himself in teaching. He announced that he had finished an illustrated anatomy in a letter to his cousin in 1592—but according to current research, Cavriani created the manuscript earlier, between 1567 and 1584. He published several historical works, but the anatomical treatise remained in manuscript format. After Filippo Cavriani’s death in 1606, the manuscript ended up in the private collection of Giovanni Giraldi and remained unknown to the world. It was not until 1752 that Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1712-1783)—an Italian botanist, physician, and librarian, who mentioned this manuscript in one of his works—brought it to light. Today, it is held by the Florence National Central Library.

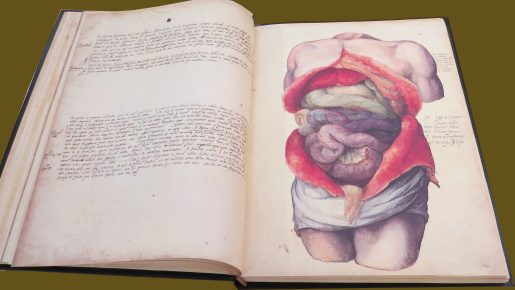

The original manuscript is in a large plano format. It is made of unfolded sheets of paper pasted on extra strips of paper. Then they are sewn together and bound in original olive-black goatskin leather, with geometric decorations in French style. It includes 70 full-page watercolor anatomical plates. The large format allowed the painter to present the true-life color and natural size of the organs. Most of the plates have descriptions in both Italian and French, while the main text is in Latin. The work is also unusual because its text is subservient to its illustrations—in contrast with the earlier tradition of anatomical works, which used images to support narration. In addition, it shows connections between natural and pathological anatomy. While discussing anatomical details based on his own dissections, case stories, and his knowledge of his contemporaries’ works, Cavriani differentiates between functions or pathologies rarely observed in a living body or cadaver (Rarum) and those considered uncommon and unusual (Paradoxon).

At the end of Cavriani’s manuscript there are four additional color plates with oil-on-paper illustrations of the eye from Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente, “De visione voce et audito.” These illustrations (attributed to the “Master of the Panels of Acquapendente”), like Cavriani’s watercolors, strictly focus on technical issues. In other words, they forgo the established tradition of blending anatomy with art.

~Gosia Fort